Archive

An aquired taste

If you do not have a penchant for reading literary novels or if you see in poetry nothing but lines of words, utterly abstruse, foolish, and unnecessary, brought together carelessly by naive poets, who might as well speak a foreign language, then you are not likely to care too much about the sequence in which words are used. But if you do like poetry, if you do like novels, then you are very likely to care about the verbal freshness of words that are used to convey meaning. After all, the plot of the Lighthouse might as well be summarized in one page, except that when some of us read it, we look for something more than just a simple story.

Of course, not all of those who spend their days savoring Shakespeare and Hugo do so because they were born with an innate talent to relish on words. The first book that was put into your hands was likely something easy to handle (mentally), and described an interesting, magical tale. But would you consider, as you grow up, that reading literature affects sensitivity to word distributions when reading texts? If the answer is yes, this, at the very least, would explain why an Anglophile abhors Dan Brown’s novels, while I, an uneducated boor, never got a knack for Shakey.

So, do we really develop an acquired taste to detect skill and beauty in literature? Do we really have the affinity to detect the small incongruities in the words others pick to make sentences, so that later we can point out to ourselves that the writer, with all his talent, must’ve used some other word to please us? Apparently, yes.

A closely knit group of researchers at the department of psychology at Stanford found that reading habits affect the judgments of writing quality. Their study rests on the premise that language is probabilistic in nature. That is, some words occur together more frequently than others, and we often can finish each others’………………..sentences because we have a preference for some chunk frequencies than others, even though there is no difference in the meaning conveyed. A briefer, yet humorous explanation is provided below:

Yes, things are not all that simple. If you do not put much relevance to the context in which language is used as it is done in the comic strip ( and which you must always do in real life!), and only look at the probabilities that define the preference for certain chunk frequencies rather than others, then you notice that if we defy those probabilities and use a somewhat odd expression, we get the feeling that something doesn’t feel right. The authors of the paper give an example:

In many ways, the idea that we pay attention to how words are used is hardly surprising. It seems obvious, for example, that “a daunting task” sounds more “right,” or more familiar, than “a daunting job.” In fact, although job is a higher frequency word than task, “a daunting task” appears over a hundred times more frequently on Google than “a daunting job.” We are sensitive to the different frequencies of the two chunks and prefer the one with the higher frequency, even though there is no real reason why a job cannot be described as daunting.

With this, Kao et. al set forth to test if “literary readers would be more sensitive to the probabilistic distributions of literary words than nonliterary readers.” They selected four and four excerpts of literary and non-literary writing and manipulated the frequencies of several chunks. They hypothesized that literary readers (those who love reading literary works) are likely to give higher ratings for passages that have higher chunk frequencies of what could be called ‘literary blocks.’ Non-literary readers would prefer reading passages that have been modified to contain non-literary chunk frequencies. Here is an example from the paper:

(a) On the further side of the field – this is the original chunk frequency suited for literary works.

(b) On the further part of the field -this is a modified chunk frequency suited for non-literary works

As you can probably notice, the meaning of both sentences is the same, but for an Anglophile the modified expression would sound odd and would make her give a lower rating. A person who reads non-literary works would likely prefer the modified chunk because he is used to seeing it more often (i.e., has higher frequency in his corpora).

As it was assumed, there was a significant interaction between the subject’s reading preferences and habits. Those who mostly read literary works gave higher ratings to original passages that have higher frequency chunks, while non-literary readers preferred mostly passages with non-literary chunks. But that is only for literary passages. For non-literary passages, all subjects preferred the originals.

Kao, J., Ryan, R., Dye, M., & Ramscar,M. (0). An acquired taste: How reading literature affects word distributions when judging literary texts. Not specified

History of the Antisocial Personality Disorder – up to 20th century

Cow, Dog, Sheep, Apple, Strawberry, Horse, Orange, Snake, Giraffe, Pear, Blueberry.

If I tell you to memorize the list of words given above, you will very likely use clustering to do that. After all, it is easy to remember something when you put it into a conceptual category, such as fruits and animals. The same process of concept formation exists when we define human behavior. When a person is belligerent, callous, insensitive and impulsive, we realize that we need to come up with a label through which we would describe these behavioral patterns that defy conventional norms. Now, for diagnostic purposes, clinical psychologists and personality disorder theorists use antisocial personality disorder as the commonly accepted term in order describe all the cognitive and behavioral patterns that through our folk psychology we attribute to sociopaths, antisocials, and psychopaths interchangeably. Nevertheless, the term did not acquire a scientific meaning overnight. What are, then, the meaning’s origins?

There is no specific date that I can list. Humans have a variety of adjectives that are very similar to what we would describe as antisocial PD, and they probably use/used them indiscriminately. A merchant who was been cheated by a customer somewhere in the 18th century would employ such expletives as knave, rogue, low-birth, villain, and scoundrel to describe the customer, while today, a citizen who is outraged by the government would rely on qualifiers like godless, blood-sucker, and fear-monger when describing a politician. These words, however, have little objective value. English language is rich in profanity and beauty, and its use is often influenced by our mistakes of attribution, us-versus-them thinking, education level, and culture. Psychology, a social science, requires a distinct definition based on observations.

Philippe Pinel, a French physician who developed a more humane approach towards the care of mental patients, noted in his Treatise on Insanity(1806) that several of his patients had a tendency for damaging and impulsive behavior. These patients, in addition to their hazardous inclinations, had an unimpaired intelligence and a full awareness about their wrongful behavior. Pinel described these patients as having la folie raisonnante (“insane without delirium” or “manic without delirium”). It is important to notice that he did not use the term in a derogatory, value-laden fashion. The definition was intended to be descriptive.

The same attitude that Pinel had towards the use of terms in describing pathologies was not shared by other physicians. For the most part, it was believed that someone who committed a morally wrong act because of dispositional factors. It was out of question to feel pity for a thief or criminal; hence, antisocials were worthy of condemnation. James Cowles Prichard borrowed some of Pinel’s findings and coined the term moral insanity, which many physicians used to show their condescension to those who had no restraint against immoral compulsions. This attitude started a confirmation bias that was prevalent throughout the 19th century, 20th century, and 21st century pathology of antisocial personality disorder.

A prime example of this confirmation bias was the work of Cesare Lombroso, an Italian criminologist who tried to link anatomical defects to antisocial behavior. Lombroso thought that criminals and other delinquents have some atavistic similarities with beasts. That is, the more beast-like you look, the more criminal you are. (A book by Samuel Robert Wells, which you can find here, has a large number of findings and drawings related to atavism). Here is a drawing that exaggerates some of those similarities:

A man with atavistic features. From: New Physiognomy or Signs of Character (1871)

Needless to say, such studies were performed in a Freudian fashion, where contradictory evidence is overlooked or neglected. The conclusions reached were of no good, too. For example, look at the drawing below. Based on arbitrary physiological differences between low and high foreheads, here is the recommendation given in Well’s book:

If thou hast a long, high forehead, contract no friendship with an almost spherical head; if thou hast an spherical head contract no friendship with a long, high, bony forehead. Such dissimilarity is especially unsuitable for matrimonial union.

A drawing showing the alleged psychological relationship between high and spherical foreheads. From: New Physiognomy or Signs of Character (1871)

Similar, absurd conclusions were reached by looking at differences between the profiles of different people and their intelligence:

Grades of Intelligence. From: New Physiognomy or Signs of Character (1871)

Luckily, at the end of the 19th century, physicians abandoned the penchant to morally classify individuals and approached the study of the antisocial personality disorder from a scientific perspective–through observation. J.L. Koch proposed in 1981 that the term moral insanity be dropped because it had a stigma attached to it and replace it with psychopathic inferiority. Eventually the word inferiority was discarded because it had a negative connotation and the term psychopathic was used (Millon et. al, 2004).

In the next post, I will talk about Demon Doctors.

The Adventures of Dr. Doubleface- OCD

About a fortnight ago I was called on an urgent visit to Wellington. As a therapist, I rarely receive calls from my patients during my off-duty hours. I make it clear, as it is required by my profession, that during my personal time I should be reached only in cases of emergency. This helps me establish a clear line between Rogerian compassion and Freudian aloofness. In the past, I often found that I was too deeply involved with the lives of my patients, and the “friendly” visits, which at times seemed perennial, have alienated me from my family. Therefore, unscheduled appointments and non-therapy related requests are acceptable only when my clients are in crisis. There is no resentment between me and my patients over this policy because we both come to an agreement right from the start of our first session on how we should deal when we meet each other in public, when the therapy is discontinued, and when they are in need.

I have, by the way, a successful practice and a background in psycho-dynamic theories. Since the early furor that kindled an interest in psychoanalysis has somewhat disappeared, I came to be more accepting of newer, more effective therapeutic methods. My background, however, should be of little interest to you. The story that I am about to relate is all that matters.

The visit that I undertook involved a client that suffered from obsessive compulsive disorder, which is commonly abbreviated to OCD. To a large extent, this disorder comes with many disabling features for those who have it: intrusive thoughts that produce anxiety and repetitive behaviors aimed at lowering anxiety are the two main ones. The individual whom I’ve visited suffered from OCD since early adolescence, and even though he went through a life full of concealment, he realized that no degree of will-power and stubbornness will save him from his obsessions, so at the age of thirty he sought help from me.

My first encounter with him was during a phone conversation. His plea for help had enough oddities in it for me to refuse his request. He offered a remuneration of $350 for a three hour session, under the condition that the sessions be held in the ambiance of his own house. Out of curiosity, and because after googling his name I was able to make the assumption that I am not involving myself in some queer affair, I agreed.

I approached his house, which by far did not resemble the generic country house estate. The windowless walls, the impenetrable metal shingles on the roof, the absolute symmetry found in all areas of his garden, and many other things that my mind was too inquisitive to notice hinted that I am dealing with an individual that suffers from OCD and not with some joker.

While I was hopping over a metal gate that would not let itself open under my efforts, a man dressed in a gardener‟s outfit suddenly appeared. I remember the questioning glances from that man, whom I thought was my patient, who apprehensively asked me:

“Are you going in?”

“Hi. Are you Mr. X?”

“No, I am his gardener. He never lets anyone in. He pays me for taking care of his garden and for signing for his daily mail, but even then I have to put the parcels in front of the main door and never enter the house. A very weird guy. But he pays well, so I don’t complain.”

Since I could not tell to a stranger the reason for my visit be-cause by doing so I would have to reveal that Mr. X is suffering from a mental disorder, I decided to partially conceal the truth, “I am a doctor, and I was called two days ago by Mr. X. From his account he is distressed by some migraines and pills are of no help. I came here to examine him.”

“Well, my other job is to not let anyone in. You see, I am also a security guy here. So you’ll have to show me something that proves that you’re a doctor. ”

I gave him my card, but he did not seem satisfied. I was fortunate to have a stethoscope and a book on medicine in my car, which are totally useless objects to me but that made an impression on the poor lad. I brought them to him, and he became less distrustful.

“Ok. I believe you. You can go in.”

As I approached the entrance, a security camera followed my every action. When I was at about two feet from the door, I heard the clanking sound of the locks. I knocked, but no one answered. I finally pushed the handle and made my way in, hoping that it would not be impertinent for me to come inside without a formal invitation. After I closed the door, I saw that the locks were controlled by a remote. In less than ten seconds I was also able to see the host.

“Hello, Dr. Doubleface. I hope that you had no trouble with my gardener. He might be simple-minded, but because I saved him from penury he is forever grateful and is able to be as cautious about my lifestyle as possible.”

“Hello, Mr. X. I certainly did not expect to enter a house with no windows. Your gardener was kind enough to let me enter, although I am not sure that he is as secretive as you think.”

“Oh, he probably mentioned that I am weird? But I am alright with his assumptions, even if he voices them. Poor, uneducated people rarely spread rumors that have any factual evidence in them. And, since it is common for them to say that scientists who are dedicated to their work are weird, no one really cares about such rumors.”

“What about your house? It can tell a lot about those who are living in it.”

“We live in an age full of eccentricities, so the design of my dwelling should surprise very few people. The reason you think my house is unordinary is because you have preconceived assumptions about me. If this were the abode of a wealthy, nuclear family, you might conclude that they have chic tastes. But since you know that someone suffering from OCD is living in it, you believe that its design betrays a lot about me.”

“You are right. I did make hasty conclusions. I was actually baffled by the fact that you shook my hand when we exchanged greetings and that the insides of your home look quite ordinary.”

“By ordinary you mean messy?”

“Yes.”

“Dr. Doubleface, there is more than one devil in hell. As you know, there are various types of obsessions and compulsions, and I am not bothered by those related to excessive hygiene. Come after me in the lab, and I will tell you who I am and what my work involves. Then we will discuss our treatment procedures.”

I followed him in his lab, and for about a half an hour we discussed matters related to his medical history. I need to mention that I have never met a more educated person before. He received a fair share of success in his life as a biochemist—a work-from-home biochemist. He made his pleasant escapes from obsessions in his home lab, to which a parcel with tissues to study was sent daily. I cannot offer you much detail here because I am somewhat re-strained and obliged to protect the privacy of my patients. Besides the fine points regarding his problems with anxiety and the tragedy which occurred during our interview, I shall delve very little on who he is and what he does.

“Dr. Doubleface, your initial assumptions about my house were correct. It has been three years since I have not left this place. I do not suffer from social phobia or agoraphobia. I could say that I am actually very comfortable around people. I get my food and other supplies through my gardener, to whom I order strictly to buy only the goods I list to him. But I do have OCD, and a very severe one.”

“Could you tell me more, then, about the nature of your obsessions?”

“Hmm…In your medical training you have probably never met a more bizarre problem than mine.”

“It’s alright. It doesn‟t hurt to tell me.”

“I obsess about weather. I have to elaborate so that you will understand me better. For my whole life I lived in the temperate region, and I got accustomed to four seasons: winter, spring, summer, and autumn. The problem is the real weather does not fit our perception of the season we are in. For example, we are now at the end of March, but the weather outside is cold enough to say that it is February. If I were to go out and experience the dank climate, I would go into a panic attack. I went outside several times, and every time I thought I was this close to being dead. As you see, because of my sedentary lifestyle I am obese, and these panic attacks have quite a toll on my heart. After I get somewhere to safety, a place separated from the outside world, I am able to regain my composure. But then I obsess about the fact that the weather out-side is not what it should be. The only way I am able to overcome those thoughts is through hours and hours of toiling in the lab. Spring has to be spring. Winter needs to remain winter. Don’t you agree?”

After his account I asked him if he had the mischance of experiencing a weather calamity, but his answer was no. Clearly I was dealing not only with OCD but with an irrational fear that had no apparent cause. My intention was to use desensitization in order to overcome his phobia of weather. We agreed about two hours in the session that he should check the weather outside through his gardener and go out only when the weather fits his perception. Then I gave him a prescription for Zoloft, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, which could help him overcome his panic attacks. At the end of our session he offered me a drink, and I kindly accepted a glass of water. He went to get one. While he was gone, I opened my bag and took out a red apple. The laboratory was cluttered with junk food, so I thought there are no restrictions about munching. While I was chewing on my apple and examining the room, I heard behind me the sound caused by glass shattering. I turned around quite startled, and I saw my host pointing his finger to my apple while shaking and shouting “Autumn! Autumn! Autumn!” He was clearly in the early stages of a panic attack. I know that in such cases there is not much that one could do. I asked Mr. X to lie down on a chair and take deep breaths. But ,before he could hear my advice, he fainted. And, his heart stopped beating, too.

I know that indirectly I am the cause of Mr. X‟s death. While I was performing CPR, I realized that apples are deciduous fruits, which under natural circumstances should be growing only in the early start of autumn. I understood that the sight of my apple caused dissonance in his mind, which eventually led to a panic attack. Paramedics got in the house a half an hour after I called them because I had trouble finding the remote used to open the locks. Because of his obesity, troubling obsessions, and panic attacks, I finally came to accept, even though it still seems as ridiculous as ever, that Mr. X died at the sight of an apple.

Why your self-interest attracts cooperation? It might be because your are percieved as a decent person.

Hombre, put a white collar and a spruce tie on. Senorita, fancy up a snappy, classy dress.

Matt Bomer (aka Neal Caffrey in The White Collar Show)

Are you done grooming? Alright. Lets do business now. But first, let me give you my credentials:

I do business with complete honesty, and I will inform you about all the profits you will earn. There will be no ulterior motives from my part: all my cards will be revealed, so you will know exactly what my next move will be. But here is the thing: in this enterprise that I have, if you seek self-interest while I maintain my honesty, you will win more money and I will get less. On the other hand, if we are both honest, then it’s 50/50 for both of us, which means that you will earn less than from being dishonest. However, there is a third scenario. I might not be as honest as I described myself, so you will once in a while get cozened by me. Eventually, you will find out that I am not at all consistent in my cooperation. Will you still decide to cooperate? Let’s find out.

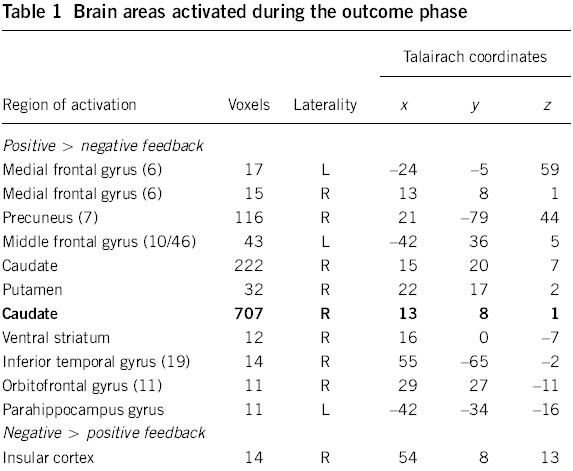

In a little experiment done by Delago, Frank, and Phelps (2005), they tried to find out the implication of the human striatum in the trial-and-error feedback processing and reward learning. Particularly interesting for them was the caudate nucleus (CN), a structure in the brain that has been linked with memory and processing affective feedback. They hypothesized that the activity in the CN increases during the initial learning process and could diminish overtime once you learn to interpret the cues from your environment correctly. Hence, CN is presumed to be an important component in guiding future actions.

In order to examine the activity of CN in people who have to make economic choices in social contexts, Delago et al. used a trust game, similar to the business deal I offered you earlier:

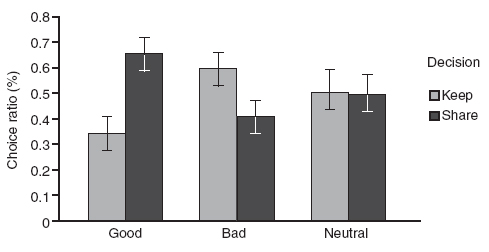

In their two-person trust game, 12 participants played with three fictional characters. In the game, participants could either keep the $1 dollar they earn from each trial or give it to their partner, who would actually get $3 instead of $1, and who would then have to make the decision to share the money or not (Fig 1). Additionally, they were presented with lottery trials, in which participants decided whether they wanted to play or not in order to win $1.50 Before the game, however, they were given specific descriptions about each fictional partner. To precis: they were instructed that one fictional partner will be good (“an English graduate student and volunteer inner-city teacher who rescued a friend from a fire during a crowded concert”), and the other two will be bad (“a business graduate student who had been arrested for trying to sell tiles of the space shuttle Columbia on an Internet auction site”) and neutral. Also, subjects were told that their partners’ responses might not always be consistent with the description given at the start of the session. Hence, a good partner might decide to keep the money instead of cooperating. Actually, during the experimental session, each partner had a 50% reinforcement rate, so there was no difference the behavior of the fictional partners.

Figure 1: a trial game was divided into a decision phase and outcome phase and could be played with three possible partners (good, bad, and neutral).

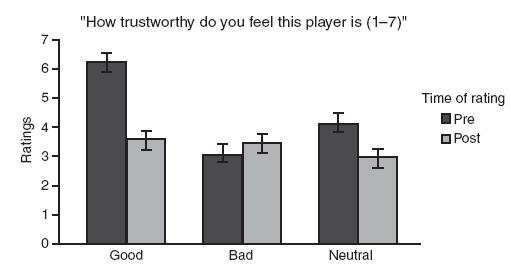

Subjects also were asked to give pre- and post- experimental trust ratings (Fig. 2) for each fictional partner, which were later compared with their overall behavioral choices and neuroimaging results.

Behavioral results:

Delago et. al found that the descriptions did change the initial perceptions of the fictional partners’ trustworthiness that the subjects made, but those perceptions withered by the end of the experimental session, mainly because subjects learned that partners were not always consistent in their response patterns. Here are the pre- and post- experimental trust ratings:

Participants were generally more likely to share with the good fictional partner than with the bad or neutral partners (Fig. 3), despite the decrease in trust in the good partner. This shows an unexpressed dissonance between the participants’ perception and their behavior. If they notice that between the good, the bad, and the neutral fictional partners there is no difference in the chosen outcomes, then why do they still make more decision to share with the good partner than with the bad?

Since participants made more decisions to share with the good partners, it is safe to presume that they were affected by the partners’ descriptions of their morality. But what is happening in their brains?

Neuroimaging results:

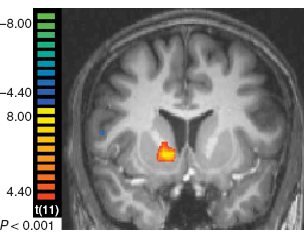

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) data was collected separately for the outcome and decision phases. As it was predicted, for the outcome phase there was a significant increase in activation in the ventral caudate nucleus, caused by the negative feedback (monetary gain) and positive feedback (monetary loss).

The significant activity in the caudate nucleus suggests that the perceived moral character influences the underlying neural activity involved in processing feedback. However, the same activity of the CN was not observed in the decision phase. During the decision phase, activation was observed mainly in the ventral striatum (VS), which suggests that VS might play a role in making predictions and anticipating outcomes.

a

White Collar Image from here

References

Delago, M. R., Frank, R. H., Phelps, E. A. (2005). Perceptions of moral character modulate the neural systems of reward during the trust game. Nature Neuroscience, 8(11): 1611-1618. http://psychology.rutgers.edu/neuroscience/publications.html

Debunking Freud Part III- Love is for Losers

This article is one of the many articles that will focus on exposing some of the fallacies in Freud’s theoretical make-up. Other posts in this series can be found through the following links:

- Debunking Freud Part I- Unconscious Homosexuality

- Debunking Freud Part II- The Origins of Male Homosexuality

Before we go on exploring the new, exciting topic in our series, let us go though a small exercise. Below you will find two links, each of which will lead you to a survey. The survey will consist of a quasi Thematic Apperception Test. Why quasi? Well, because I came up with it on the spot, and I have not the slightest idea if it will measure or reveal what I think it is supposed to measure. So, mesdames et mesdemoiselles, click on Lola to proceed. Gentlemen, you follow Bugs.

___

The quasi TAT test you went through, assuming that you did, was cued to make you identify with a person of the same gender as you in order to describe the feelings and thoughts about a loved one. Each picture in the test was chosen so that you would perceive a slight imbalance in the rapport within the couple. Hence, those who clicked on the picture with Lola saw a man genuflecting in front of a woman, while those those who clicked on Bugs saw a man holding a woman on top of him in a slightly leisurely (and maybe even sexy) way. Thus, I hoped to show through those photos that one partner shows more love to another (not that I think that I was successful in that endeavor).

So, how does this small exercise tie with Freud? Freud had a very nasty, Hobbesian view about humans. For him even such a sentiment as love is not an emotion that stems out of selfless desire. On the contrary, Freud considered that love is essentially selfish, and that any exceptions to this are the result of the superego overcoming the id. In the Freudian realm, when we mention something related to love, we are essentially talking about object-love. When the infant comes to this world and later develops an identity, anything that gratifies or thwarts his needs is considered an object. So, objects include not only such mundane, inanimate concepts as chairs, tables, etc., but also animate concepts, e.g. mother, father, dog…

As the child interacts with his world, some objects gain more significance than others. The amount of importance an object gains is proportional to how well it satisfies the id of the child. Hence, because mothers are highly nurturing, children see them as important objects. Moreover, because some objects are more important than others, they tend to receive more libido, a type of emotional investment from the part of the child. Because of this libidinous investment, for Freud love is considered more like an instinct that helps the child survive.

In his book on narcissism, Freud came to even a more unconventional conclusion that might have outraged those who consider love as a pure emotion. This is what he said:

Loving in itself, insofar as it is longing an deprivation, lowers self-regard, whereas being loved, having one’s love returned and possessing the loved object raises it once more.

What he means is that you feel good and happy as long as you’re loved, and you subject yourself to abjection once you start loving someone. Loving is for losers and being loved is for cool guys(and girls).

Fromm, a renown philosopher and psychologist, did not like the whole love-object affair. He fought that there is no such thing as “love-object.” For him love was an inner activity, where the loved ones become part of who you are, and that speaking of someone you love as being an object is simply strange and materialistic.

I do not know if Freud’s conclusion about love are scientifically valid. I think that Sternberg’s Triangular Theory of Love has more evidence behind it that explains at least partly some intricacies related to love. Nevertheless, Freud’s theory is highly appealing. Try to remember a time when you loved someone and that love was not returned. How did you feel? I am sure that this is not a sentiment that you would like to experience again. Now, if you are among the lucky Freudlings, try and recall how you felt when you were loved? Did you, at some point, feel that maybe the person who loves you is somehow owned by you? If yes, then maybe through the TAT test you might have revealed that you do see loved ones as objects.

References

Freud, S. (1914). On narcissism: An introduction. The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud. London: The Hogarth Press.

Fromm, E. (1980) Greatness and limitations of Freud’s thought. New York: Harper & Row Publishers. {The book was originally published in Germany under the title Sigmund Freud Psychoanalyse–Grosse und Grezen}

Perlman, E. (1986). Introduction: Narcissism and Object Choice in Freud British Journal of Psychotherapy, 3 (1), 60-64 DOI: 10.1111/j.1752-0118.1986.tb00955.x

Debunking Freud Part II- The Origins of Male Homosexuality

This article is one of the many articles that will focus on exposing some of the fallacies in Freud’s theoretical make-up. Other posts in this series can be found through the following links:

1. Debunking Freud Part I- Unconscious Homosexuality

—-

Leonardo da Vinci and Sigmund Freud. Photograph: Hulton Archive/Getty Images and Bettmann/Corbis

Freud’s personal views on homosexuality, if compared to what his contemporaries believed, were liberal. According to a response letter he send to a mother who was worried about her son’s homosexual behavior, he thought that homosexuality was neither a vice nor a degradation, but something most normal people experience:

Homosexuality is assuredly no advantage, but it is nothing to be ashamed of, no vice, no degradation; it cannot be classified as an illness; we consider it to be a variation of the sexual function, produced by a certain arrest of sexual development. Many highly respectable individuals of ancient and modern times have been homosexuals, several of the greatest men among them. (Plato, Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, etc). It is a great injustice to persecute homosexuality as a crime – and a cruelty, too.

(I am not a graphologist, but after comparing this letter to a page of a letter sent to Fliess on September 21, 1897, which I found in Peter Gay’s biography about Freud, the handwriting seems authentic. )

Although Freud was a maverick in theorizing, how did he come to accept homosexuality as a natural part of our sexual development? From what I gather, everything started with the man who made this painting:

The Mona Lisa

In 1910, after about a year from his trip to the US, Freud decided to write something on Leonardo da Vinci. The outcome of that decision was a novelette whose purpose was to expose a psychoanalytic study on Leonardo. Freud acknowledged that this endeavor was very tentative and his findings were based on a scarcity of biographical materials. Nevertheless, he established the framework of his book on a rumination about childhood that Leonardo left in one of his notebooks. Freud took that childhood contemplation and elaborated an artistic interpretation from it. First, here is Leo’s legacy to Freud:

It seems…that I was destined to occupy myself so thoroughly with a vulture, for it comes to my mind as a very early memory that, as I was in my cradle, a vulture came down to me, opened my mouth with its tails, and stuck me many times with its tail against my lips.

Freud, who was an erudite in religion and history, knew that the symbol for vulture was a hieroglyph for mother in ancient Egypt. Since Leonardo was an illegitimate child, Freud called him, romantically, the “vulture child.” Later on, Freud speculated that Leonardo had a very affectionate mother, and that passionate maternal love, coupled with the experience of not having a father, had an important influence on is early development. However, because of the over-protective and excessive love from her mother, Leonardo was subjected to too much femininity, which set the stage for his homosexuality. But that explained only the inception process of homosexuality. Full blown homosexual behavior comes later on in life, after the child finally becomes an adult and tends to repress his love for his mother and inadvertently identifies with her. Additionally, another important factor that plays a role in becoming a homosexual is anal eroticism. Anal eroticism comes from a fixation during the anal stage of psychosexual development.

This theory about the origins of homosexuality seems far-fetched. It was based on a vague account that Leonardo left behind, to which Freud found mainly an artistic interpretation. The book is replete with lyricism, so its appeal is understandable. Nevertheless, the conjectures Freud made are not entirely scientific.

The Evidence

In order to give some validity to Freud’s claims, we need to find if there is any evidence that support the fact that males from the homosexual community had (1) careless or missing fathers, (2) overly affective mothers, (3) strong maternal identification, and (4) some characteristics that relate to anal fixation.

1&2. Is there a presence of an intimate relationship with the mother and lack of intimacy with a father in a male homosexual?

A summary of the studies pertaining to this question has been included in a book by Fisher and Greenberg. Most of the studies tried to find a correlation between homosexuality and early childhood experiences by using questionnaires. Braaten and Darling (1965) did a study on thirty four homosexual and control samples of college students by using questionnaires and MMPI. Their conclusions support Freud’s assertions: the mothers of homosexuals had an intimate relationship with their sons, while fathers were mainly detached and showed little attention to them.

Nevertheless, some studies (Terman & Miles, 1936; Jonas, 1944; O’Connor, 1964) found that the relationship between the fathers of homosexuals and their sons often contained a great deal of hostility, even brutality, which could at least hint us that there might be another explanation why homosexual men have such strenuous relationships with their fathers (Will you love the hand that hits you?). Additionally, most of the studies described by Fisher and Greenberg have used convenience samples from psychiatric yards, or samples that had an interest in establishing Freud’s validity (in Bieber et al. (1962) surveys were delivered to psychoanalysts who were asked questions about a large sample of homosexual men that they have treated), which significantly diminishes their external validity. Also, none of the studies examined the cultural component of homosexuality. Maybe fathers detested or ignored their homosexual sons because society does not approve homosexual tendencies and expects them to react coldly or brutally to it? This would mean that parents’ behavior could be the result of their child’s homosexuality and not, as Freud suspected, the other way around. Still, considering that these are correlational studies, no type of causal link can be inferred about the relationship between homosexuals and their parents.

3. Does the male homosexual child identify with the mother?

Objective evidence in these respects is almost nonexistent. I found only one study by Chang and Block (1960) that shows identification with the mother among male homosexuals. In the study, Chang and Block gave to twenty male homosexuals and twenty controls a list of adjectives and asked them to describe which of them could be attached to the following concepts: ideal self, mother, father, and self. They found that homosexuals gave themselves similar adjectives they gave to mothers. A series of summaries of other studies in Fisher and Greenberg, while focusing on the identification question, looked at the masculinity-femininity dimension. (That is why Braaten and Darling (1965) have employed MMPI, because it looks on the aspect of femininity-masculinity.) They found that homosexual men are more feminine than heterosexual men. Even so, there is not enough evidence to substantiate that the score on masculinity-dimension is also a measure of identification.

4. Are homosexual men anally fixated?

There is no evidence of anal fixation or anal eroticism.

Conclusions

So, most male homosexuals do have hostile relationships with their fathers and intimate relationships with their mothers. But this correlation tells us nothing about the origins of homosexuality. The hostile or indifferent attitude from fathers could well be the result of the child’s homosexuality. Evidence showing identification with the mother and anal fixation is scarce and rarely corroborates Freud’s theory.

Can you guess who is the man with the cigar?

References

Braaten, L. J., & Darling, C. D. (1965). “Overt and covert homosexual problems among male college students.” Genetic Psychology Monographs, 269-330.

Jonas, C. H., (1944). “An objective approach to the personality and environment in homosexuality.” Psychiatric Quarterly, 18.

O’Connor, P. J., (1967). “Aetiological factors in homosexuality as seen in Royal Air Force psychiatric practice.” British Journal of Psychiatry, 16 .

Terman, L. M., & Miles, C. (1962). Sex and personality. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Debunking Freud Part 1- Unconscious Homosexuality

This article is one of the many articles that will focus on exposing some of the fallacies in Freud’s theoretical make-up. I shall try as much as possible not to bring any ad hominem attacks against Freud and delineate the difference between his opinion as part of a theory and his opinion as part of his personal belief system, even though there is considerable overlap between the two:)

Martin, although a relatively affluent person who has had a great deal of accomplishments in his life, felt that his existence was not worth all the material belongings he bought over the years, and that his relationships with other people, which he considered less fulfilling because they were based on collegiality and not on affinity, brought him no pleasure. In order to ease this gradual downturn in his life, Martin decided to seek the help of a psychoanalyst.

Over the course of several weeks Martin shared his life story with his therapist. Eventually the relationship between him and the therapist progressed to the level where Martin had absolutely no restraints in telling and retelling some of the worries that continuously vexed him. After a month or two of treatment, when the sufferer-healer relationship was well established, the psychoanalyst decided to probe Martin about his sexual behavior. Martin, lying on the soft, therapeutic couch, who now fully trusted the bespectacled person behind him, told everything he knew, as candidly as one possibly could do:

“I had a great deal of women in my life. Some of them have kindled some interest in me, but for the most part the attraction was sexual. There was a time, when I was in my 20s, that I wouldn’t spend one night without a woman in bed. Quite frankly, I felt a lot of pleasure from these encounters, and did not have second-thoughts about experimenting when it comes to sex. Even now I am sexually very healthy.”

While Martin tells his account, the session is suddenly interrupted by the practitioner’s secretary. Apparently, against all conventions, the healer has to leave the room to attend to some important matter. Martin, bored, notices that the therapist left his notes behind. Unable to restrain his curiosity, he picks up the notebook filled with scribbles and leafs to the last page. He reads:

“Possibility of unconscious homosexuality.”

After the therapist comes back, Martin indignantly throws the notebook in his face. “I am not gay!”…. While he slams the door, the psychoanalyst picks up the notebook and writes this final note:

“unconscious homosexuality in the patient confirmed.”

—

The account above, although fictional, reveals through the psychoanalyst’s behavior Freud’s reaction towards repressing homosexual drives. According to Freud, when a patient experiences a very intense heterosexual life, it can be argued that this intensity helps repress unconscious homosexuality. Moreover, if you as an individual do not experience even a slight attraction to other persons of the same-sex, then this complete absence of attraction is another proof that you are unconsciously repressing your homosexuality. The problem with this explanation is that it is unfalsifiable. If Martin would argue with his therapist and continue to defend his heterosexuality, then the rejoinder from Freud would be that Martin is rationalizing and is further repressing his homosexual drives. So, Martin is left with the choice of denying his sexual attraction to other men and thus proving that the therapist is right or with accepting his homosexuality and again validating Freud’s claims. No win-win game here.

Additionally, Freud believed that this unconscious homosexuality comes to surface in subtle ways. For example, if a man praises another man’s suit, then this could be evidence of unconscious homosexuality. Also, if a man likes to spend his time in the company of other men in a non-sexual way, then we have more evidence of repressed homosexual penchants. On this theoretical framework, Freud at one point considered that monks are particularly prone to unconscious homosexuality.

In the next post we will review Freud’s personal views about homosexuality and the evidence related to the theoretical view that support/falsify Freud’s claims about the origins of homosexuality.

References

Freud, S. (1962). The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud. Vol 3. J. Strachey, (Ed.). London: Hogarth.

______ (1964). Leonardo da Vinci and a memory of his childhood. New York: Norton.

Fromm, E. (1980) Greatness and limitations of Freud’s thought. New York: Harper & Row Publishers. {The book was originally published in Germany under the title Sigmund Freud Psychoanalyse–Grosse und Grezen}